『北极海冰的融化速度比气候模拟所预测的更快。这是为什么呢?』

Climate change in the Arctic:beating a retreat

北极气候的变化:不应打退堂鼓

Sep 24th 2011| from the Economist

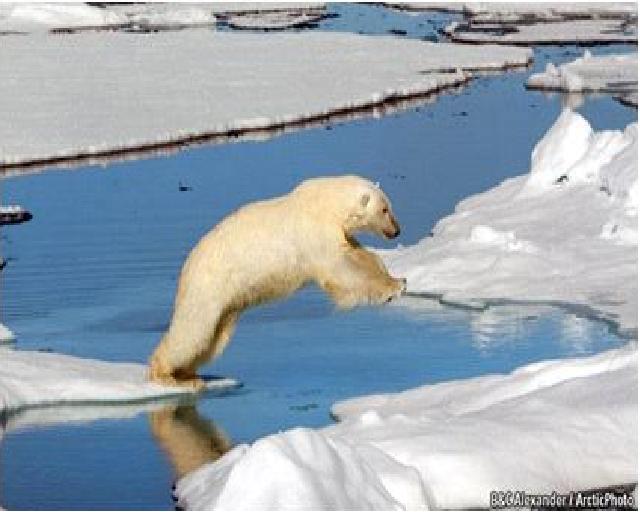

That Arctic sea ice is disappearing has been known for decades. The underlying cause is believed by all but a handful of climatologists to be global warming brought about by greenhouse-gas emissions. Yet the rate the ice is vanishing confounds these climatologists’ models. These predict that if the level of carbon dioxide, methane and so on in the atmosphere continues to rise, then the Arctic Ocean will be free of floating summer ice by the end of the century. At current rates of shrinkage, by contrast, this looks likely to happen some time between 2020 and 2050.

The reason is that Arctic air is warming twice as fast as the atmosphere as a whole. Some of the causes of this are understood, but some are not. The darkness of land and water compared with the reflectiveness of snow and ice means that when the latter melt to reveal the former, the area exposed absorbs more heat from the sun and reflects less of it back into space. The result is a feedback loop that accelerates local warming. Such feedback, though, does not completely explain what is happening. Hence the search for other things that might assist the ice’s rapid disappearance.

One is physical change in the ice itself. Formerly a solid mass that melted and refroze at its edges, it is now thinner, more fractured, and so more liable to melt. But that is (literally and figuratively) a marginal effect. Filling the gap between model and reality may need something besides this.

The latest candidates are “short-term climate forcings”. These are pollutants, particularly ozone and soot, that do not hang around in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide does, but have to be renewed continually if they are to have a lasting effect. If they are so renewed, though, their impact may be as big as CO2’s.

At the moment, most eyes are on soot (or “black carbon”, as jargon-loving researchers refer to it). In the Arctic, soot is a double whammy. First, when released into the air as a result of incomplete combustion (from sources as varied as badly serviced diesel engines and forest fires), soot particles absorb sunlight, and so warm up the atmosphere. Then, when snow or rain wash them onto an ice floe, they darken its surface and thus cause it to melt faster.

Reducing soot (and also ozone, an industrial pollutant that acts as a greenhouse gas) would not stop the summer sea ice disappearing, but it might delay the process by a decade or two. According to a recent report by the United Nations Environment Programme, reducing black carbon and ozone in the lower part of the atmosphere, especially in the Arctic countries of America, Canada, Russia and Scandinavia, could cut warming in the Arctic by two-thirds over the next three decades. Indeed, the report suggests, if such measures—preventing crop burning and forest fires, cleaning up diesel engines and wood stoves, and so on—were adopted everywhere they could halve the wider rate of warming by 2050.

Without corresponding measures to cut CO2 emissions, this would be but a temporary fix. Nonetheless, it is an attractive idea because it would have other benefits (soot is bad for people’s lungs) and would not require the wholesale rejigging of energy production which reducing CO2 emissions implies. Not everyone agrees it would work, though. Gunnar Myhre of the Centre for International Climate and Environmental Research in Oslo, for example, notes that the amount of black carbon in the Arctic is small and has been falling in recent decades. He does not believe it is the missing factor in the models.

The rapid melting of the Arctic sea ice, then, illuminates the difficulty of modelling the climate—but not in a way that brings much comfort to those who hope that fears about the future climate might prove exaggerated. When reality is changing faster than theory suggests it should, a certain amount of nervousness is a reasonable response.

热门推荐:

考研网校哪个好

新东方考研培训班

考研培训班

考研培训机构哪个好

考研英语网络课程

文都考研网校

北京考研培训班