『卡扎菲死后,利比亚新格局正在形成 。』

A new timetable

利比亚现状 — 新的时间表出炉

Oct 29th, 2011 | from The economist

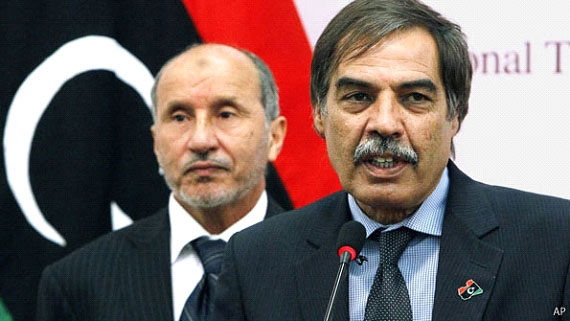

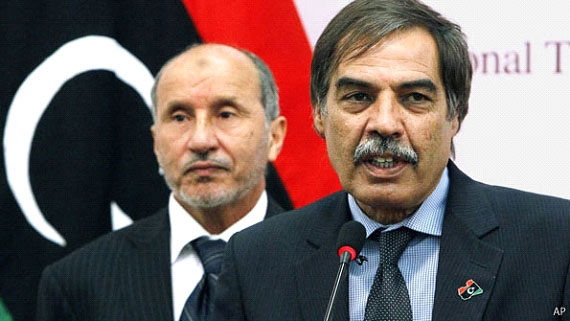

WHEN Libya’s new rulers declared on October 23rd that their country, with the fall of Sirte and the death of Muammar Qaddafi, had definitively been liberated, a constitutional-cum1-electoral clock began to tick. First, within a month, the chairman of the current National Transitional Council, Mustafa Abdel Jalil, is to appoint an interim2 government. Within three months it should pass preliminary electoral laws. And within eight months Libyans are to elect about 200 delegates to an assembly charged with3 drafting a constitution to be approved by a referendum4 within another year, meaning mid-2013. Once the constitution is endorsed5, elections for a parliament and later for a president will follow.

Unlike neighboring Tunisia6, which already had a constitution worth amending7, Libya is starting from scratch8, since the colonel abhorred9 such things. In a speech to announce Libya’s liberation, Mr Abdel Jalil said the country’s laws would be based on sharia1, that “usury2” would be banned and polygamy3 allowed. This dismayed4 many secular-minded5 Libyans, who chided6 him for pre-empting7 decisions that will be the purview8 of the constituent assembly.

Mr Abdel Jalil commands9 respect both from Islamists. But he may find it hard to maintain harmony between factions10 as they draft a constitution. Proceedings in the council have been tense since the killing in July of Abdel Fatah Younis. Since then, the avuncular11 chairman has held things together12. “It is very important that the council sticks to its timetable and that no one prolongs it,” says Guma el-Gamaty.

But rushing things may create problems, too. Libya has no licensed political parties and no formal forum yet for discussing the future in a constructive way. They cannot be created overnight. As elsewhere in the region, the Islamists seem better organised than their secular rivals13.

The first step must be reining14 in the plethora15 of paramilitary forces that are basking in their triumph over Colonel Qaddafi and integrating them into a fledgling16 national army. This too will take time. Many of the militias have ferocious local loyalties. Abdel Hakim Belhaj, an Islamist who commands Tripoli’s anti-Qaddafi forces, has proposed a plan to draw the revolutionaries into a new army and police force.

Meanwhile, the former head of the council’s executive committee stepped down17 on October 23rd. His deputy, Ali Tarhouni, who holds the oil and finance portfolios18, is set to replace him. But the Misrata faction is also lobbying for one of its own to have the job. Mr Abdel Jalil’s future is also unclear. He previously said that he too would step down once the liberation was declared. But many people hope—and guess—he can be persuaded to stay on as a calming influence.

Rivalry between Benghazi and Tripoli for control of the oil sector persists. Libya’s oil men are getting production back on stream a lot faster than many expected. Investors are already returning in droves1 but it is not yet clear who is empowered to oversee the contracts. Such uncertainties are inevitable2 in the early days of the new order. But some ministries, including those in charge of energy and finance, are already running quite well. Compared with Iraq in the days after the fall of Saddam Hussein, Libya is in much better shape3.

热门推荐:

考研网校哪个好

新东方考研培训班

考研培训班

考研培训机构哪个好

考研英语网络课程

文都考研网校

北京考研培训班