『欧洲法院(ECJ)规定,基于对人类胚胎使用的干细胞技术不能获取专利。』

European science stemmed

干细胞研究在欧洲受严格限制

Oct 19th 2011| from the Economist

ANY country, you might think, would relish being able to call itself the world’s leader in scientific research. America and Europe, however, seem to be in a bizarre parallel contest: which can make its scientists' lives more difficult by imposing the most muddled rules. This week the European Union edged ahead. On October 18th the European Court of Justice (ECJ), the highest court which opines on EU-wide matters, ruled that methods to derive embryonic stem cells could not be patented. The ruling sets Europe apart from the rest of the world—even America, long averse to stem-cell research, has no such qualms.

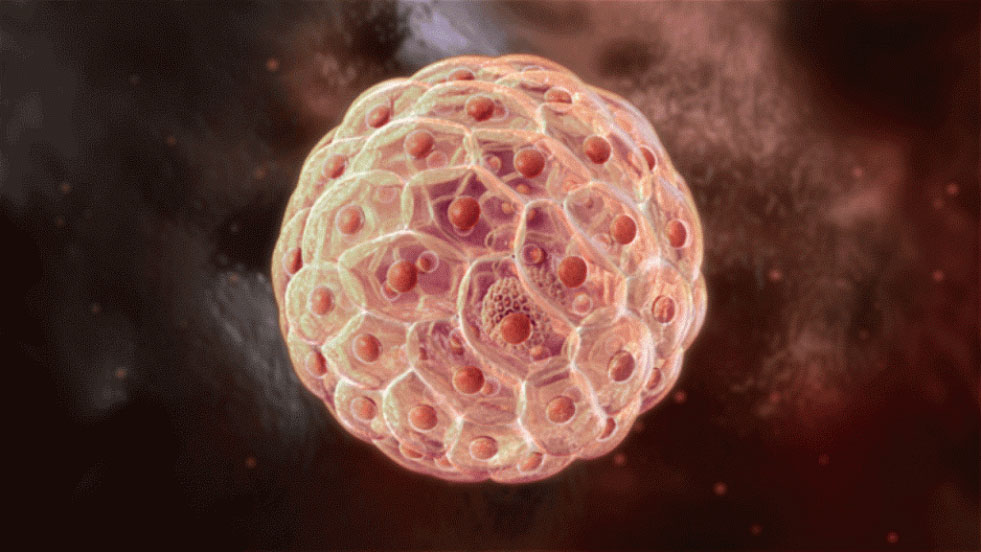

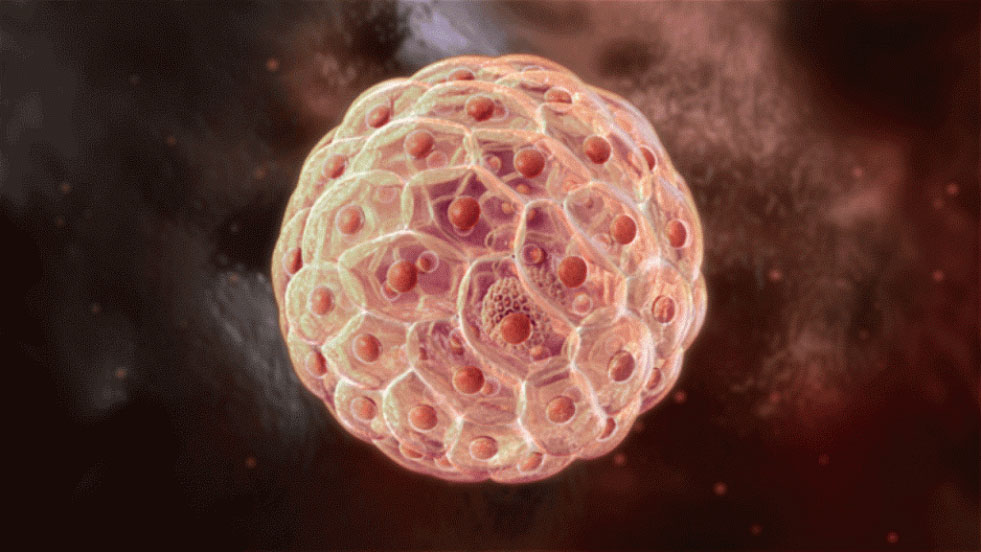

The decision concludes a suit from Germany. In 1997 Oliver Brüstle, of the University of Bonn filed a patent for a method to create neural precursor cells, which go on to develop into fully functional mature nerve cells. Dr Brüstle's method derives these precursors from human embryonic stem cells. The hope is that they could eventually be used to treat degenerative conditions like Parkinson’s disease. The rub is that extracting embryonic stem cells involves destruction of human embryos.

However, Dr Brüstle’s challenger was not, as might be expected, a pro-life activist. It was Greenpeace, an environmental group, though its main objection, to what it says is the commercialisation of human life, does have a religious ring to it. The ECJ agreed, deferring to a directive that bars patents “where respect for human dignity could thereby be affected”. Any process that involves the destruction of the human embryo, the court declared, cannot be patented.

The ruling has sparked immediate uproar among academics. The decision, they warn, will not just undermine basic research. It will prompt companies to funnel cash to more welcoming jurisdictions, such as South Korea, Singapore or China, or deter them from investing in the field altogether. Others are more sanguine. Alexander Denoon, a lawyer at a law firm specialising in biosciences, argues that such a decision was augured by an earlier one from the European Patent Office in 2008. He thinks that firms and scientists should be able to adjust without abandoning research completely. Besides, European researchers can still seek patents in America and other countries.

In the near term, however, confusion will reign. Much depends on how lower courts and patent offices interpret the ECJ’s ruling. The decision may not damn stem-cell research, as some more excitable boffins fret. But it will certainly nobble its European practitioners.

热门推荐:

考研网校哪个好

新东方考研培训班

考研培训班

考研培训机构哪个好

考研英语网络课程

文都考研网校

北京考研培训班